These writings are offered freely, but donations help to keep the lights on … 🕯️

Do not go to the Garden of Flowers… June 3rd 2023.

At the end of our lives

when we think of our most devastating pain

what will matter is how much we were still able to love.

– Leda Rafanelli Djali –

. . . in your Body is the Garden of Flowers

I do not lead yoga retreats to Costa Rica or Bali because if we cannot learn how to take refuge in our own hearts right here, right now, under these circumstances and in this place, then how will we ever be truly free?

We live in an era when the consequences of human insatiability have reached apocalyptic levels. It’s time to think twice about spewing fossil fuels across the globe and contorting other people’s home communities into gentrified tourist destinations in order to locate a sense of peace and fulfillment in ourselves.

As the true gravity of human neurosis comes to a head through ecological devastation, economic oppression, mass shootings, entrenched bigotry and fresh tyranny, we would do well to consider turning to mind-body practice not solely as a reprieve or a getaway but as a radical restorative framework to transform our day-to-day lives into something we do not feel we need to escape from. If we engage the philosophy and the practices of yoga skillfully, we can transform our daily lives into a source of nourishment, connection, and mutual freedom.

The 15th century Indian mystic and yogi poet, Saint Kabir, wrote:

Do not go to the garden of flowers!

O friend! go not there;

in your body is the garden of flowers.

Take your seat on the thousand petals of the lotus,

and there gaze on the Infinite Beauty.

Far more than a fitness exercise or a stretching regimen, yoga is the oldest spiritual technology in the world for developing the mind and actualizing wholeness from within. The practice guides us to uncover an innate way of seeing and of being in the world that is simple, deep, sustainable, and in selfless service to all beings. Yoga as the founders intended it could not possibly be more relevant or more urgent as we enter the eleventh hour for the planet, the lives of our children and grandchildren, and the world’s most vulnerable human and non-human communities.

Mind-body practice is meant to familiarize us with access points to an inborn relational space that is a wellspring of solace, joy, and freedom of spirit not dependent on favorable conditions and, to the contrary, that relishes the ordinary and becomes ever more luminous when we rise to the challenge of accessing it in moments of discomfort, distress, and hardship. The daily work is to clear a well-worn path to this place until there is no need for a path.

The great Zen Master Dogen Zenji remarked, “When we first seek the truth, we think we are far from it. When we discover that the truth is already in us, we are all at once at peace in our original selves. If you cannot find the truth right where you are, where do you expect to find it?”

Dogen, founder of the Soto school of Zen in 13th century Japan, wrote a famous manual called Instructions to the Cook. A practical guide for anyone who cooks for a monastic community, it is simultaneously a treatise on how to use all of the ingredients available to you in your life to create the most nourishing meal possible to feed your own spirit and to support the well-being of everyone around you.

With this poignant and practical analogy, Dogen sums up the central thesis of yoga: The deep fulfillment of spiritual liberation comes not from getting what we want but from realizing what we have and from sharing it with each other.

Using the simple, precious, limited, and imperfect ingredients of our day-to-day lives, it is within our power to make of our lives what Zen practitioners call “the supreme meal.”

Dogen imparts to us that the key to becoming a good cook is to employ the practices of yoga to cultivate sanshin, the three heart-informed mind states: Magnanimous Mind (daishin), Nurturing Mind (roshin), and Joyful Mind (kishin).  Daishin: Magnanimous Mind (also called Big Mind)

Daishin: Magnanimous Mind (also called Big Mind)

Cooks with Magnanimous Mind work with what they have, not with what they wish they had.

When we do a mind-body practice like yoga, tai chi, qigong, meditation, prayer, or spending time in nature, we generally come to the practice feeling tense, uptight, defensive, fixated, stressed, or overwhelmed. By the end of the practice, we feel a sense of ease, expansion, clarity, compassion, and fundamental okayness. What changed?

By grounding ourselves in our body and our breathing, we come back to timeless presence. Dwelling in the intimate aliveness of the here and now, we feel connected, and our hearts open.

The loudspeaker of our ruminative mind gets turned down or turned totally off. The mental babble of reactive, worried, judgmental, irritable, and dissatisfied narratives and doom forecasts decreases in volume and so our mind becomes a calm, peaceful place where we can see things more clearly and process things more wisely.

In mind-body practice, the hallucinatory and isolating dark woods of our ruminative mind (small mind) comes into contact with the quiet expansive mountain-top clarity and open-hearted connectedness of spacious awareness (Big Mind).

If we learn to connect with Big Mind on a consistent basis through practice, we become less captivated by small mind’s dour predictions, cynical conclusions, and urgent agenda to demand perfection out of every situation and out of everyone, including ourselves.

Our choices and our actions become more rooted in the life-affirming values of Big Mind, such as having patience with the process, trusting in our own agency, recognizing the limits of our control, moving at a sustainable pace, making time for joy and rest, exercising compassion and wise understanding towards each other and towards ourselves, and staying connected to the fleeting preciousness of this unique experience of being alive.

Greater familiarity with Big Mind brings greater familiarity with small mind’s attempts to drag us like a riptide into disconnection, rejection, and distortion of the world within us and around us. We see small mind’s propensity for dissatisfaction and constant craving for things to be better or different than what they are. We no longer heed our thoughts, or even our perspectives, as being the gospel truth. We let go of needing things to always be a particular way. We see how foolish it is to expect life to revolve around our every wish, desire, preference, and expectation. We allow this moment to be what it is. We allow ourselves to be as we are. We allow others to be as they are.

At the center of mind-body practice is coming to terms with the reality that dysfunction, discomfort, discontent, difficulty, limitation, loss, change, and death are inescapable and inevitable. It is a special kind of freedom to release the tension of resistance and reactivity to how things are. This is what is meant by Magnanimous Mind.

This is also how Magnanimous Mind gives way to Nurturing Mind. Authentic compassion and care arise from the big picture understanding that life is complicated, that we all struggle, that we are not all shaped by the exact same education, guidance, resources, and support, and that perfection or constant forward progress is a preposterous and sometimes aggressive expectation.

All beings require love and support, encouragement and forgiveness to get even a glimpse of awakening. The best we can do is to be as gentle, as generous, and as supportive as possible with each other and with ourselves.

When we are able to see past small mind’s dissatisfaction and delusions of control, we find not only that what we have is enough, but that what we have is immensely precious and utterly satiating.

One of the oldest yoga texts in the world, the Bhagavad Gita (first millennium BCE), reads:

When the mind comes to rest,

restrained by the practice of yoga,

free from longing and dissatisfaction,

it becomes as serene and luminous

as a lamp in a windless place.

Beholding the self by the Self,

the yogi unbinds the bonds of sorrow

and rests in Self.

She who is steadfast in yoga

knows the Infinite Joy

of not deviating from the truth

that the Self is present in all beings

and that all beings are present in the Self.

In this unity, we can never be lost. Roshin: Nurturing Mind (or “Parental Mind”)

Roshin: Nurturing Mind (or “Parental Mind”)

Cooks with Nurturing Mind take great care of all things and do not distinguish between self and other. Dogen instructs cooks to handle the ingredients of life “as if they were their own eyes.”

Roshin literally means “Old Mind,” referring to the care of a parent or a grandparent for a child. It is the deep abiding care of mature love that is not conditional or transactional.

Feelings of being loved and of belonging are innate and irreducible human needs. Humans are hard-wired for connection, physically, emotionally, cognitively, neuro-biologically, and spiritually. Absence of this fundamental need leads to mental and physical health issues, increasing the likelihood of disease and premature death in humans by 200%, according to the medical research of renowned heart specialist Dr. Dean Ornish.

Nurturing mind recognizes that the root of delusional and destructive behavior is suffering, ignorance, and the illusion of separation and isolation. Therefore, Nurturing Mind loves for the sake of its own transformative power.

Nurturing Mind holds a fundamental caring regard and wish for the healing, awakening, and well-being of all beings, independent of approval or disapproval of their words, behaviors, and actions. Just like a healthy parental love, Nurturing Mind as a matter of course is an agent of accountability, compassionate discipline, healthy boundaries, and skillful justice.

Martin Luther King, Jr., who was deeply influenced by the yoga tradition and the spiritual activism of its greatest social change leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Thich Nhat Hanh, said, “What is that good that is productive and produces every other good? I am convinced that it is love. I am convinced that love is the greatest power in all the world. Love has within it a redemptive power. There is power there that eventually transforms individuals and communities. If you hate yourself, you have no way to redeem yourself. If you hate your enemies, you have no way to redeem your enemies. There is something about love that builds up and is creative. There is something about hate that tears down and destroys.”

Nurturing Mind is cultivated from the inside out. Learning to genuinely care for yourself in thoughts, words, and actions enables you to fully accept the love of others and to radiate it outward selflessly and effortlessly.

The great yogi Nisargadatta Maharaj said, “All that you need is already within you, only you must approach yourself with reverence and love. Self-condemnation and self-distrust are grievous errors. All I ask of you is this: make love of yourself perfect.”

We can be surrounded by people who demonstrate love for us, but if we do not extend adequate love and care for ourselves, we are like a leaky bucket. The love and the care that gets poured in from others drains out through the wounds of self-harm such that we remain depleted and walled off.

Lama Justin Von Bujdoss points out, “It is difficult to love and to be uptight at the same time. Freedom is openness. Love is a way of opening.”

The open-hearted compassion of Nurturing Mind is as potent as sunlight when it shines in all directions. Everyone thrives exponentially in its glow. When we learn to inhabit Nurturing Mind through practice, we become less inclined to maim ourselves and others with the slings and arrows of harsh judgment. We become instead a medicinal hub of care, generosity, and kindness that transfers to everyone and everything around us.

When we are rooted in Nurturing Mind, moments of personal depletion, adversity, illness, or trauma are easier to heal and recover from. Nurturing Mind frees us to be more present and more genuinely attentive to the suffering and the struggles of others.

This is how Nurturing Mind gives way to Joyful Mind. Nurturing Mind introduces us to the joy of self-tending, the joy of healing, the joy of giving, the joy of loving without limits, the joy of being free to be present to the simple moments in life.

Nurturing Mind is the heart-informed mind of the Bodhisattva who views self-liberation as indistinguishable from collective liberation. Mature love unlocks the suffering of human constriction, and freedom is the joy of openness. Yoga is the practice of freeing ourselves from internal systems of oppression in order to disarm external systems of oppression. “The function of freedom,” asserts Toni Morrison, “is to free someone else.”

Kishin: Joyful Mind

Kishin: Joyful Mind

Cooks with Joyful Mind have realized the most fundamental insight of meditative practice: that we live together with all beings and are not separate; that connection is the root of joy and fulfillment; that to fully realize the truth of interconnectedness is to have boundless gratitude and affection for the preciousness of life.

The modern industrial and technological age is driven by the nihilism and dissatisfaction of small mind. Heavily dissociated from the natural cosmos and from humanity, it steams through life like a locomotive, fueled by compulsive consumption, leaving destruction in its wake, propelling us faster and faster along, until both we and the planet are completely emptied out. Whatever destination we are so hell-bent on, do we know we are blazing through paradise?

In having access to too much, in filling our days with too much, in expecting too much of ourselves and each other and the world, we generate a kind of clutter, a kind of speed, a kind of mania, a kind of numbness that stifles our capacity to simply exist, to be in communion with life, to enjoy the small wonders of life that are all around us.

I don’t need to go on yoga retreat to Costa Rica because I can lie in the grass in my own backyard and find complete enlightenment in the close up view of a honeybee tending to the hundred tiny trumpets of a single clover flower.

Another word for Joyful Mind is “whole-heartedness.” When we can bring our minds into clear calm stillness, when we can rest in our natural disposition of attention and affection, appreciation and compassion, we feel whole in our hearts. Everything we experience, we experience with our whole heart. Everything we do, we do with our whole heart. Everything we give, we give with our whole heart.

This inner luminosity of spirit enables us to persist in the coldest and darkest of places, and it eases the hearts of everyone we come into contact with. When we prioritize a daily practice of contacting inner peace, we become a refuge for ourselves, for our loved ones, and for all beings.

The great Zen master D.T. Suzuki said, “When we start to feel anxious or depressed, instead of asking, ‘What do I need to get to be happy?’ The question becomes, ‘What am I doing to disturb the inner peace that I already have?”

The deep fulfillment of spiritual liberation comes not from getting what we want but from realizing what we have and from sharing it with each other.

What we all cherish so much about spending time in nature is that it brings us back to this place in us. It slows us down to the pace of connection. Nature is our physical and spiritual mother. It tunes us to a way of being and of experiencing that deep down we know we are meant to inhabit. It calls us back home and reminds us of our birthright, the intimacy of interconnection.

I’m not sure that this has ever been captured so well than it is in Passionist Priest and Buddhist scholar Thomas Berry’s poem, “Appalachian Wedding”:

Look up at the sky!

The heavens so blue

the sun so radiant

the clouds so playful

the soaring raptors

woodland creatures

meadows in bloom

rivers singing their

way to the sea

wolfsong on the land

whalesong in the sea –

celebration everywhere –

wild, riotous

immense as a monsoon

lifting an ocean of joy

then spilling it down

over the Appalachian landscape

drenching us all

in a deluge of delight

as we open our arms

and rush towards each other

all of us moved by that vast

compassionate curve

that brings all things together

in intimate celebration –

celebration that is

the universe itself.

Enlightenment is all-natural. March 1st 2023.

Nature is constantly luring us towards the enlightened state.

– Shinzen Young

The rising of a new year stirs in many of us a desire to renew our lives in some way, to do some decluttering and to engage in practices that bring a sense of freshness and new growth.

One way that we can reinforce and harness this wholesome energy is to explore a daily meditation practice.

Meditation gives us the ability to guide our decluttering projects all the way down to the very core of our being. We can clear our heads, lighten our hearts, and tend to our souls with a small measure of quiet time each day to connect with what is going on inside us and to draw closer to life.

In some parts of the world, these early months of the year are associated with Vassa, or a “rains retreat,” when the wet weather makes the roads less passable and so instead of traveling outwardly, one travels inwardly by way of prioritizing contemplative practice.

Similarly in this part of the world, these late winter and early spring months are an ideal season for preparing the ground for an inner garden, a quiet regenerative space where we can rest, renew, and access inner clarity, courage, compassion, authenticity, and interconnectivity throughout 2023.

The profound health benefits of meditation continue to be borne out by the burgeoning field of neuroscience and, likewise, the profound health benefits of spending time in nature. It is no surprise to me that the science greatly overlaps in how each exerts a healthy influence over the body, the brain, the nervous system, and the psyche.

Simply put: nature meditates us.

Just like in meditation, time spent in nature brings us back to a felt sense of homecoming, a kindred and consummate inner harmony where we feel connected to something greater than can be expressed in words.

Like meditation, nature connects us to a spaciousness expansive enough to reflect back to us our fullness, our wholeness, and the fullness and wholeness of life.

Just like in meditation, nature draws us into the richness and clarity of this moment by awakening and enlivening our senses.

Just like in meditation, nature silences the ruminative mind and awakens the luminous mind, creating the right conditions to experience inner freedom, liberative insight, and big Aha! moments.

Albert Einstein said, “I think 99 times and find nothing. I stop thinking, swim in the silence, and the truth comes to me.”

If you have ever felt drawn to meditation as a daily or weekly practice, but have also felt discouraged and intimidated by it, you are not alone. Finding any amount of inner silence in which to wet your toes, much less swim around in, can feel near to impossible for most of us.

It’s actually quite normal to feel overwhelmed and flustered during meditation practice by the seeming inability to shake the mind’s compulsion to ruminate, analyze, plan, self-judge, fantasize, problem solve, and otherwise engage in continual mental noise. In fact, this is precisely why meditation is so important.

In light of this universal attraction-repulsion towards meditation, let us reflect on that strong intersection of meditation and time spent in nature. Because, right there, where your love of spending time in nature and your attraction towards meditation intersect, lies a direct path to inner stillness.

The magic and the deep peace that we experience in the natural world can also be found right here inside of us (after all, we are also nature), and we can learn how to contact it at will through meditation practice. What’s more, the natural world teaches us how to contact that place, at any time, indoors or outdoors, in easeful circumstances or in times of great distress.

Our relationship with the natural world unfolds through our six sense gates.

The Buddha identified not five, but six sense gates: taste, smell, sight, sound, body (as in touch and felt sensation in the body), and mind (through the mind we experience mental phenomena and thought stimulus).

The living flow of the natural world opens and expands all six sense gates, integrating and sharpening our faculties for consciousness and for connection, for in-sight and for expansion, all by soliciting awareness at the level of our senses.

The potential for awareness resides at each of our six sense gates. By learning to focus through our senses at will, we generate balance between the thinking mind and the luminous mind. In other words, we gain the freedom to sideline mental chatter in favor of other ways of knowing, of experiencing, and of being.

In order to see a star in the nighttime sky, you often cannot look directly at it. Because of how our eyes are designed, we sometimes have to look off to one side a bit, using our peripheral vision to bring the star into focus. Quieting the mind is just like that. Instead of actively trying to control or cease our thinking, the mind calms indirectly as we engage and focus through our senses.

If the mind was a tumultuous pool of water where someone just did a cannonball, the best way to still the pool would be to allow it to gradually calm on its own. We would need to disengage with the water so as not to further disturb it or stimulate it. So too will our thoughts gradually settle and our mind gradually clear, all of its own accord, if we continually shift our attention away from compulsive rumination and towards sensory awareness.

Like any skill, concentration and sensory clarity require dedicated practice to strengthen and master. As we gradually heighten our concentration skills, mental chatter and rumination become more transparent and less captivating, the mind becomes less agitated, and we can access experiences of tranquility, openness, freedom, insight, and expansive, equanimous states of consciousness.

Sometimes when we are immersed in nature, we feel as though we are touching the very heart of life. Meditation practice can help us to reside there as often as possible, in motion and at rest, in times of ease and in times of great adversity, driving down the highway or washing the dishes, helping a friend or helping a stranger, in conflict and in isolation, watching TV or reading the newspaper, in times of overwhelming change, grief, illness, and even on our deathbed.

It is the awakening of consciousness and primordial awareness through the sense gates that nature so magically solicits; and likewise it is our senses that can light the path to that clear luminous stillness within.

Small moments, many times. December 5th 2022.

May you awaken to the mystery

of being here

and enter the quiet immensity

of your own presence.

John O’Donohue

As we approach Winter Solstice, when nature becomes quiet, dark, dormant, and still, let us be reminded that inner peace and contentment blossom from the bare bones of simplicity. We could, this winter, shrug off the hypomanic holiday agenda and instead match our inner rhythm with the rhythm of nature, assuming the pace and quietude of a forest blanketed in snow.

On these cold, dark days we could warm ourselves to the core in savoring simple everyday gifts: a hot shower, a warm homemade meal, sunlight through the window, an afternoon nap, a cup of tea, a small kindness, moon and stars in the crisp evening air, deliberate quiet time unassailed by screens and scrolling, calendars and social pressures.

In filling our days with too much, in having access to too much, in expecting too much of ourselves and each other and the world, we generate a kind of clutter and a kind of mania that stifles our natural disposition to simply exist, to behold and to be held in the consummate tranquility of luminous presence with all that is.

Inner luminosity of spirit is what enables us to persist in the coldest and darkest of places, it refreshes and heals our bodies and minds, it eases the hearts of everyone we come into contact with.

In the Lotus Sutra, Gautama Buddha says, “Light up your corner of the world. Make it clear where you are.”

The value of simplifying our lives is that it makes lighthouses of us all. When we make choices that prioritize inner peace, a natural joy springs up in our hearts, and we fortify our capacity to be a refuge for others.

“When you become yourself, Zen becomes Zen.” Which is to say, when you allow yourself time and space to rest in the center of your being, every action you take in the world will be more skillful, more joyful, more easeful, more compassionate, and more harmonious.

In the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha emphasizes each individual’s responsibility to shepherd their inward light, not as a syrupy sentiment, but as a daily disciplined practice that has the power to bring healing to the whole world. With each practice we become one less source of aggression and reactivity in the world, and one more source of levity and generosity.

All that is being asked of us is a little time each day to clear out the inner clutter and connect with life. Whatever fraction of a pause we can spare in a day — 2 minutes, 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes — to just breathe, to listen in silence, to rest ourselves, to tend to our suffering, to come home to being alive, to practice undoing as the foundation for all of our doing.

The prescription for our condition is simply small moments, many times. And yet, the Buddha warns in the Lotus Sutra that even though we know the antidote, we become too addicted to the poison to procure it’s remedy. And so it is that the best gift we can give each other and ourselves this holiday season is the gift of less rather than more. Let our carts be empty but our hearts be filled with the rare jewels of simplicity. Let us free each other and ourselves from the oppression and the violence of too much.

In winter, nature invites us to rest and convalesce in the silence and the darkness, to rekindle our inward light while we await the rebirth of the sun. One of the oldest known prayers in the world still calls out to us —

Oh grace of Earth, Fellow Beings, and Sky,

Let us meditate on the light of the Sun

– Illumination that gives life –

May we awaken that radiance within ourselves.

Gayatri Mantra 1700 BCE

The End of the World as We Know It. March 7th 2024.

The only wisdom we can hope to acquire

is the wisdom of humility: humility is endless.

T.S. Eliot

For the last eight months I’ve been learning to live with disability, coming to terms with the sudden and unexpected worsening of my Long-Covid which, after years of mostly high-functioning remission, relapsed this past summer worse than ever before with fresh new features of ME/CFS.

I can’t help but see the dark irony in being the yoga therapist always harping on about how we all need to slow down and rest, only to be struck with an illness that demands relentless rest, vigilant pacing, and high stakes energy math.

I measure how well I’m doing day to day by how my body tolerates walking up the steps in my house to the second floor. Though I’ve experienced considerable improvement in the last few months, people twice my age have far more energy and physical capacity than I do on most days.

It’s possible I may never be able to hike again. I may never have the stamina to visit my brother in Serbia. It’s possible I could end up far worse than I already am with the next Covid infection or stressful life event.

It’s possible also that I could continue to improve, learn new ways to manage my illness, find a treatment that helps, and at some point be able to live a life beyond the considerable constraints I have now.

The future seems more uncertain and unknowable than ever before. I feel most at peace when I am able to rest in a sense of compassionate acceptance that makes room for both deep grief and open-hearted optimism.

I think many of us feel that way about the state of the world right now.

My health is fragile and tenuous, as are living conditions for a growing number of people, as is our democracy, as are international relations, as is the health of the planet. We are collectively confronted with the glaring reality of impermanence and the steep consequences of living beyond our limits.

Being a disabled person in a culture that insists on limitlessness and perpetual growth is very eye-opening. We are so deeply driven by our conditioning to perceive limitation not as something that life can and does require – something to be expected, respected, and taken care of – but as something that must be overcome, outsmarted, out-spiritualed, and defied at all costs.

We are not a culture that puts the slowest hiker first, or that cherishes the most fragile among us, or that organizes itself around the most vulnerable. The story our culture likes to tell is that there are no true setbacks, only tests of character.

Even as the sad remains of the runaway train of human exceptionalism and exploitation is running us ragged, running people over, and driving the planet to its doom in the name of unbridled progress and life without limits, we’re all still convinced we just need to keep tweaking that special formula that proves our worthiness and our exemption from suffering.

bell hooks wrote, “One of the mighty illusions of our culture is that all pain is a negation of worthiness. That the real chosen people, the real worthy people, are the people that are most free from pain.”

But pain is how nature communicates limits. Pain tells us we need to slow down, pay attention, and take care of something. Pain tells us it is time to stop, before we do further harm to ourselves or to others. Pain teaches us to listen.

It could be a physical pain in our body, the heaviness of grief, the frantic sizzle of overwhelm or anxiety, the emotional pain of our partner or loved one, the pain of dying creatures in a rapidly warming ocean, the pain of oppressed, exploited, ignored, and marginalized people.

Experiencing pain, our own pain and other’s pain, is how nature teaches us humility, empathy, and compassion. If we are so deeply pain-averse, so afraid to admit to ourselves and each other that we are in pain, so uncomfortable witnessing and being with pain, so convinced that pain is a signal of weakness or something that only happens to people less capable and less worthy, then what does that reveal about our deeply conditioned values as a society? How are these dysfunctional values contributing to the harmful and catastrophic events taking place in our world, in our local communities, in our families? How might changing your own personal relationship with pain and with limitation have an impact on your loved ones, on our entire society, on our entire world?

Lama Rod Owens writes, “Systems of oppression and violence will never end or be challenged until we as individuals can hold space for our own pain.”

For me, at this time of both personal and collective apocalypse, I’m keeping my eyes turned toward the jewel in the lotus – om mani padme hum – the only true riches in this world are the ones that issue forth from a heart that can bloom in the muck of suffering.

Wisdom, humility, compassion, luminosity, and liberation are the hard-earned gifts of respecting limitation and listening to pain. We can learn to care for and respect our own pain and our own limits. We can learn to care for and respect each other’s pain and each other’s limits. We can learn to care for and respect the Earth’s limits and the Earth’s pain and that of all of its creatures.

The most consummate joy that humans can experience is the joy of connection, mutual support, cherishing, listening, learning together, and belonging. It is the only wealth you can take with you to your sick bed, to your death bed, and to the world’s end.

Kyong Ho, a 19th century Korean Zen master, wrote, “Do not wish for perfect health. In perfect health there is arrogance and greed. So an ancient said, ‘Make good medicine from the suffering of sickness.'”

Unwell-Being & Perceiving the World’s Sounds. September 23rd 2022

Perhaps everything that frightens us is,

in its deepest essence,

something helpless that wants our love.

– Rainer Maria Rilke

Sometimes there is no consolation. No wise words to hear or to say. No Mary Oliver poem or Rumi quote that doesn’t sound grating or trite. Nothing that can touch that between-the-worlds feeling, that detached numbness, that all-consuming pain, that groundless disorientation.

In the age of wellness, where does the experience of unwell-being fit in?

I contemplated this a great deal while Randy and I suffered our way through our second big Covid infection. Thanks to the vaccine, we didn’t get as frighteningly ill this summer as we did in 2020; but even so, we were quite sick for several weeks, largely incapacitated for over a month, and even now feeling the faint echoes of brain fog and fatigue and respiratory irritation.

There are experiences in life that can turn everything upside down and leave you feeling stupefied and impotent and adrift. The usual consolations and coping strategies don’t seem to apply. Major illness, loss, death and dying, depression, trauma, severe anxiety, violence, prolonged pain, and spiritual crises are all experiences that can submerge us in an in-between-the-worlds state that resists swift or easy resolution or relief. Unsolicited advice in these moments becomes a naive insult.

Sometimes what is being asked of us is to submit to a kind of natural stasis, suspension, inertia, unknowing, and even dissolution.

Mind-body practice is meant to prepare us for these states, even as it helps us understand how to nurture states of well-being.

I once had occasion to meet a Zen master. He gave a talk on how to nourish qi, or life-force energy. He then gave a talk on the common stages one might pass through on the path to awakening through meditative practice. During the Q & A, a woman asked, “what effect does progression through the stages have on overall health?” She was angling towards the notion that each phase might confer some kind of health benefit or supernatural immunity. He answered, “As you progress through the stages of enlightenment, you will gradually become less attached to your health.” He then gave a talk on death and dying.

The wellness industry is mostly well-meaning up to the point where it reinforces toxic worldviews of the dominant culture, which is riddled with death-phobia, vulnerability-aversion, and discomfort-avoidance. Harrowing experiences like death and dying, major illness, grief, psychic upheaval, trauma, and prolonged pain can become complicated or compromised by the conditioned pressure to not be that way, and so to strive to overcome it, and the internalized condemnation of domination culture which perceives any non-peak state as failure, weakness, hyper-sensitivity, laziness, or incompetence.

The drive to become a “better you” or the “best you” may actually be your worst adversary and saboteur in times of great need and grueling transformation. It is worth investigating who desires and defines a “better you” and what is being lost on the chopping block. Perhaps it is the very least of you – the insecure, flawed, unwell, fearful, unknowing you – that is humble enough, honest enough, and tender-hearted enough to seek out and stumble its way into the healing places during the most trying moments of your life.

Learning to have a skillful relationship with well-being requires that we also develop an intimate relationship with ill-being. We must learn to “suffer well,” as Thich Nhat Hanh says. If we come to our spiritual and mind-body practices only with the notion to improve ourselves or improve our condition, what of those times when our condition cannot be improved, or when we are, so to speak, at our worst? Should we not also apply our practices to learn how to be with the discomfort in ourselves and in the world that cannot be remedied, escaped, or avoided? To learn how to meet ourselves just as we are, right where we are, without pressure or condemnation?

This is what I contemplated at the height of my illness.

What I heard in response was crickets.

That is not to say that I heard nothing, but maybe a kind of nothing.

Lying in bed with excruciating body aches and bad memories of heart issues from my first experience with Covid, my attention relaxed for a moment and I became aware of the sound of crickets outside my window.

Inside me, the pain was a loud, chaotic, all-consuming noise, but outside there was this pervasive sound of quiet tranquility. The gentle all-is-well sound of the crickets kept company with the sound of my pain and anxiety so that the latter became less engrossing. The pain was there in my body, but I rested also in the peaceful body of the earth humming with crickets.

The Bodhisattva of Deep Listening, Avalokiteshvara (in the masculine form) and Kuan Yin (in the feminine form), is the Perceiver of the World’s Sounds. As the story goes, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, listening deeply, perceives the cries of all who suffer and, profoundly moved in the heart, releases them from suffering by way of great compassion. If we also listen deeply, we can hear Avalokiteshvara’s voice in the five True Sounds:

🪷 The first sound is the Wonderful Sound. This is the sound of the beauty of life and the kinship we have with all beings and the natural cosmos. By becoming aware of the crickets, I was able to hear the Wonderful Sound.

🪷 The second sound is the Sound of the One Who Perceives the World. This is the sound of deep quiet. It is the silence required in order to listen deeply. It is the quieting of mental chatter and fixation.

🪷 The third sound is the Brahma Sound, the sound of the place in us where we are connected to everything and the sound of everything as it exists in us.

🪷 The fourth sound is the Sound of the Rising Tide. This is the sound of the heart flooding with compassion. It is the sound of the collective compassion of all spiritual friends and ancestors, wisdom teachers and lineages, becoming a rising tide that is capable of raising and uplifting all boats.

🪷 The fifth sound is the Sound that Transcends all Sounds of the World. It is the sound of living truths that can only be experienced through silence, and cannot be spoken or repeated. Alan Watts put it this way: “You cannot get the water of life into neat and permanent packages; you cannot walk off with a river in a bucket.” The fifth sound is the sound of direct experience and insight that transcends words and concepts.

Avalokiteshvara, in a sense, is the Bodhisattva of Unwell-being. When we are in-between-the-worlds, outside of the reach of the usual consolations and comforts, stupefied, impotent, adrift, deeply unwell — or when someone we love is in this place — we can turn to the wisdom of Kuan Yin and do nothing more than listen in the quiet.

Kuan Yin does not try to fix it for anyone, nor does she come up with wise and nice-sounding words to say, nor in any way does she attempt to alter external conditions. Pushing and pulling on external conditions is the primary way that most of us learn to seek relief and approval, distraction and satisfaction. And while this can at times be effective, and at times necessary, there are also times when we are very limited in being able to change or improve our own or someone else’s state of being by pushing or pulling on circumstances. In those moments, we are forced to simply be. To be in the experience we are having.

Mind-body practice is meant to help us uncover our capacity to simply be here. When silence and stillness have a place to sit inside of us, even a tiny place, we have the power to listen. We can be in the present moment, without pushing or pulling. We can be with our friend who suffers, without pushing or pulling. We can be with the one inside of us who suffers, without pushing or pulling. Seeing clearly what is there, the heart will eventually open so that compassion and connection arise.

While I was on meditation retreat with Shinzen Young in late spring of this year, I hit a wall in my practice. For almost an entire day I could do nothing but sit with an epic, nameless fear. In undergrad school I worked in daycare, so I sometimes think of meditation practice as putting children down for a nap. All of the compulsive and boisterous voices in me need to be sat with, acknowledged, listened to, and sometimes comforted in order for them to feel calm enough, safe enough, and properly persuaded that rest is a good idea, enabling us all to enjoy a quiet and expansive tranquility.

But I could not budge the nameless fear.

Mostly I just wanted it to not be there. It felt heavy and suffocating, and I was embarrassed that I had it. I was afraid that nothing could penetrate it and that that was proof that it was the only true thing. It felt like the final remaining curtain between me and a penetrating peace, and it was an iron curtain that simply wouldn’t drop.

I often encounter a point in my meditation practice when I realize I am trying to squirm away from some uncomfortable part of my experience by willing the force of my mindfulness skills to make it go away. A lot of people think that is what meditation practice is for and clearly there is a part of me that also fancies that misconception. The distinction is that when you use your practice to will something uncomfortable away, it will hide in the closet and come back as an even bigger bogeyman. When you use your practice to acknowledge it and welcome it to be there, a kind of alchemy occurs in which the uncomfortable thing becomes permeable, transforms itself, becomes benign, or vanishes completely.

When I finally caught myself condemning and shying away from the towering fear, I turned directly towards it and allowed myself to sit right in the middle of it. I welcomed it. Sit with me.

It was then that I heard these words: fear is love.

I could feel at the heart of my paralyzing fear was a deep caring — my care and my fear for my life, my care and my fear for my loved ones, my care and my fear for this planet, my care and my fear for so many beings. Focusing on the feeling of deep care at the heart of my fear drew the experience of love to the foreground and the fear subsided.

At the root of all suffering is the cold iron curtain of fear. An experience of deep care warms and softens and opens the heart. The iron curtain drops. Where fear isolates, love connects.

Kuan Yin, Avalokiteshvera, the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion, is also known as the Bestower of Fearlessness. We can see why. It is not difficult, now, to connect the dots. We know both names mean the same thing.

Not the fearlessness in western culture of being tough enough and powerful enough to hit back harder. This is, rather, the fearlessness of non-aggression. The fearlessness and fierceness of a courageously raw, tender, and open heart. It is the fearlessness that comes from the actualization of true compassion.

Kuan Yin comes to the aid of those in fearful, pressing, and difficult circumstances, bestowing fearlessness through great compassion and deep listening. As the poet Rilke writes in his Letters to a Young Poet, “perhaps everything that frightens us, in its deepest essence, is something helpless that wants our love.”

The wondrous voice, the voice of the one

who attends to the cries of the world.

The noble voice, the voice of the rising

tide surpassing all the sounds of the world.

Let our mind be attuned to that voice.

Put aside all doubt and meditate on the

pure and holy nature of the regarder

of the cries of the world.

Because that is our reliance in situations

of pain, distress, calamity, and death.

Perfect in all merits, beholding all sentient

beings with compassionate eyes,

making the ocean of blessings limitless,

before this one, we should incline.

~ Chapter 25 of The Lotus Sutra

Suffering and Sourcery. April 8th 2022

I stroll up the stream

to its beginning

and sit watching the clouds.

– Wang Wei –

“All I teach is suffering and the cessation of suffering,” said the Buddha. And so, when we do not know what to do with pain, with heartbreak, with ill-being, and with witnessing the suffering of others, meditative practice can be a sanctuary for entering into relationship with our distress and for touching the sources of healing.

Prayer, meditation, mindful movement, and quiet time in nature are all mind-body rituals that allow us to step outside of the forward press of time and bring mind and body together to touch the source of being. Through these quiet inward moments we are re-source-d. We renew body, mind, and spirit, and we gather the resources that we need to be more fully present to the struggles and joys of everyday life.

What does it mean to touch the Source? It means to come back to the beginning, to return to the place in you and in the world that is fully intact, fully realized, unwounded and untarnished, and can in no way be diminished. We follow the stream back to the headwaters, back to where we feel whole and connected, clear, and at peace. Mind-body practice is meant to guide us to that place where we can drink from the source.

Many of us can relate to the experience of touching the beginning, of touching the source, when we spend quiet time in nature. I cannot describe in words for you why gazing at the rippled expanse of the St John’s River makes me feel so utterly pacified, so complete. Watching tree limbs sway in the breeze, the feeling of warm sun on skin, the sound of rain tumbling from cloud to tree to ground, the nighttime sky deep with stars — the shapes and rhythms of nature are unsurpassable comforts that touch something deep in us beyond words or concepts.

Time spent in nature brings us back to the well of being, yes, but nature is also in us. We touch the source when we touch this breath – YHWH – and feel it and follow it from beginning to end. The organic shapes and rhythms of nature reside right here in the flow of our breathing. When we struggle or suffer, when the world seems chaotic or irredeemable, we can come back to ground zero: the primordial rhythm of expansion and contraction, the global respiration of living energy, the oceanic waves of in-breath and out-breath.

In a moment of witnessing our own and others’ suffering, we may be limited in our capacity to remove it, but we can face it, and we can find refuge by simplifying our experience all the way down to being with this one breath. I move away from my overwhelm by moving toward my present moment experience at the pace of one breath at a time. I have the power to take care of this moment.

Like a tree swaying in the breeze, I allow myself to be taken in by the peaceful sway of my breathing, a gentle, reliable, ever-present rhythm that can help to carry me through this experience.

Our re-source-ing practices do not so much qualify us to conquer struggle and ill-being or transcend difficulty and darkness as they help us to be with them from a place of inner sanctuary and with a propensity for transformative alchemy.

The great Zen master Shunryu Suzuki said, “The only way to endure your pain is to let it be painful.” Cruel or morbid though this may sound, what he is in fact describing is a profound act of courage and compassion. To witness the pain and to be with the fullness of the pain is to come to terms with it, to give it space to be there, to get to know it and understand it, and to allow our full concern and compassion for it to propel us toward healing and mitigating action.

There are so many difficult experiences in life that we cannot avoid. We endure sickness and limitation, and the changes and losses of aging. We must face our own death at some unexpected hour. We lose people and places and things that we love. We are a victim, a perpetrator, a witness to human cruelty, greed, and unthinkable violence. We have bad nights of sleep. We harbor painful personal insecurities. We are thrust into the bruising muck of conflict with partners, friends, family, bosses, co-workers, and communities dear to us. We struggle with a lack of resources, financially or socially or energetically. We get knocked off balance even on good days by irritating intrusions, overwhelming circumstances, and groundless earth-shaking moments when the whole world turns upside down.

Life exacts what it exacts, regardless of who you are, how you eat, how much you exercise, how much wealth is at your disposal, whatever you think life ought to be like, and whatever heights of spiritual insight or intellectual prowess you believe you have attained. 2/22/2022 at 2:22 pm did not jolt us into an upgrade reality where humans are “more evolved,” where it’s all light and love, and where we only get the good stuff. Neither did Hale-Bopp but still somehow the expectation remains.

The great wheel of cause and effect, of ignorance and imperfection, of impermanence and interdependence keeps turning, keeps churning out individual, interpersonal, global, and societal grace and harm, boon and consequence, creation and destruction, beauty and horror, joy and suffering. Mind-body practice is not our ticket out. There is no ticket out.

Our re-source-ing practices are here to help us come to terms with this reality. The urge to transcend, escape, analyze, forecast, despair, sugarcoat, or rise above our discomfort and distress is a fundamental unwillingness to face our fear of how things are. It is a kind of procrastination that fosters protracted dissonance. It is a refusal to feel the humbling vulnerability of the limits of our control. It is turning a deaf ear to the call to listen deeply for the skillful action that can be taken to yield the most benefit in accordance with what is happening.

Unfaced fear and the quest for invulnerability fosters neurosis and aggression. It prevents us from being here, together, in this world, engaging the fullness and nuance of this experience. Our resistance to being with the hard stuff plunges us deeper into dissociation, craving, delusion, and latent suffering while leading us further away from an open, wakeful, consummate connection with life and with death.

Discomfort and distress are flares sent straight up out of somewhere inside us or in the world that needs to be brought to the surface, held in the light, skillfully tended, and thoroughly understood. The desire to rid ourselves of what makes us feel vulnerable or uncomfortable is a shying away from the messy, humbling, and necessary labor that growth and transformation require and that compassion and love demand. Love is not a victory march; it’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah, sang Leonard Cohen.

Where we tend to conflate difficulty and darkness with weakness or failure, we might instead see it as a common crucible by which we learn and re-learn how to listen, how to love, how to abide, and how to let go.

The capacity for the human mind and heart to open into the togetherness of not-knowing but of cherishing is another way to say having the humility, the courage, and the wisdom to continue to open deeper into love above all else, especially in the face of what most unsettles us. We touch the headwaters, we touch the Source, when we feel the truth and the importance of our connection to each other, and when we extend deep listening, compassion, patience, and mercy to ourselves and to all beings.

The fundamental atmosphere of all mind-body practice is one of relaxed, patient welcoming, unconditional befriending, unrelenting compassion, and attentive inquiry into how things are. This is because of all the capabilities that human beings can possess and develop through practice there is none more transformative and paramount than an open mind and an open heart.

Discomfort and suffering are not static experiences. They are fluctuating interpretations. When we tense up around the current interpretation, we concretize it, magnify it, and reinforce it. We tense up against ourselves, against each other, and against the world. This tension narrows our field of perception, grips and bottles our emotions, locks and constricts our bodies, and terrorizes our nervous system. The tension itself can quickly become a much greater problem than the source of it. We box ourselves in, and so we suffocate.

We can touch the beginning, we can touch the Source, by disrupting our tension and our reactivity. Mind-body practice, in a very practical and literal way, teaches us how to release tension, how to relax fixations, and how to ventilate emotions.

The Tibetan word for equanimity is tang-nyom: tang = let go, nyom = equalize. When we feel ourselves tensing up, fixating, and suffocating, we need to take time to let go and equalize. Not only is it okay, but it is necessary to return to the headwaters of ease and relaxation where we can see, feel, and respond to suffering and struggle more skillfully. Your tension and your anxiety are not required proof that you care enough, nor are they an elixir for the suffering in the world, in yourself, or in your loved one.

Relaxation can be an expression of and a pathway into love. By taking the time and the care to free ourselves of physical, mental, and emotional constricting, we make room for healing and calm clarity to come in. By embodying relaxation, everyone around us feels welcomed into greater ease.

Meditation master Shinzen Young asks this interesting question: “How can we use nothingness in the service of everythingness?” In other words, how can our emptying out be a way of entering in?

Instead of worrying about how it might end, a Sourcerer takes care of the present by continually returning to the beginning. To be with the discomfort and suffering in life requires sourcery: the practice of drawing power and peace from the headwaters.

Loving what is here. January 16th 2022.

Do not try to become anything.

Do not make yourself into anything.

Grasp at nothing.

Resist nothing.

– Ajahn Chah –

As we cross the threshold into 2022, please consider that in this very moment you are enough as you are. You are completely whole. Nothing to add. Nothing to subtract.

When you see yourself in this way, feel how it resolves you into a state of self-trust and self-fulfillment. Feel how it centers you in your gifts and your goodness. Notice how compassion so naturally, so generously arises when you are at peace with yourself.

A seed, in a sense, is already a tree. The full tree potential is already there inside of it. It knows exactly how to be a tree, it is capable of tree-ness right then and there, as a seed. The right conditions and the proper nourishment will allow it to bring itself to full fruition, to actualize what is already there.

Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj said, “All you need is already within you, only you must approach yourself with reverence and love. Self-condemnation and self-distrust are grievous errors. All I ask of you is this: make love of yourself perfect.”

This could, to some, sound self-indulgent,

Just like the seed and the tree, when you bring the right nutrients in, when your basic needs are met, you thrive, and growth happens all on its own. Creativity, insight, inspiration, and motivation arise organically and spontaneously.

When you learn how to properly support and nourish yourself (rather than maim yourself with slings and arrows of self-loathing and self-sacrifice) you shine like the sun when you are at full strength, and in moments of depletion, adversity, or hardship, you heal and recover more fully and more efficiently.

Your sense of wholeness, care, and kindness toward yourself transfers to everything and everyone around you. You are more present to others and to life, more joyful and energetic, more inspired to be generous with your time that has been freed up by no longer driving yourself to exhaustion, by no longer being preoccupied with the neurosis of warring with yourself.

A tree cannot grow if it is deprived of water, so to do we dry out and become vulnerable to dis-ease when we plow forward relentlessly, underestimating

A tree cannot grow if it is deprived of oxygen, so too do we suffocate ourselves by trying to force an agenda from the outside, fueled by impatience, impossible standards, harsh self-judgment, and fear that we won’t measure up.

When you judge and condemn yourself for how you are faring and how you are feeling, you are no longer on your own side. You are not at peace with yourself. You are waging an internal battle, the outcome of which will always be you being defeated. Forcing yourself to feel how you “should” feel, be who you “should” be, and do what you “should” do, is a kind of violence, a kind of self-aggression.

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche reminds us that “aggression is the source of our problems, not the solution.” He also said that “the ultimate bravery is to be unafraid of yourself.” Being unafraid of yourself means loving yourself as you are, trusting in your own needs, in your own rhythms, in your capacity for redemption, especially on the days when you are not feeling well or faring well, when you are tired and depleted, when you are not at your best, when you are struggling, when you need a time out from the world. Especially on those days, you are worthy of your own love, kindness, and patience.

Martin Luther King, Jr said, “What is that good that is productive and produces every other good? I am convinced that it is love. I am convinced that love is the greatest power in all the world. Love has within it a redemptive power. And there is power there that eventually transforms individuals. If you hate yourself, you have no way to redeem and transform yourself. If you hate your enemies, you have no way to redeem and transform your enemies. There is something about love that builds up and is creative. There is something about hate that tears down and is destructive.”

Trying to “change yourself” by way of external force yields only temporary, superficial changes, while exacting lasting harm. Deep and enduring transformation arises out of faith, love, honesty, patience and trust in yourself.

Unafraid of yourself, you are able to come into honest, inquisitive

In 2022, may we learn the value of loving what is already here. May we come to understand it as the only path to lasting transformation. Rather than make new year’s resolutions to “better yourself” in 2022, consider instead reflecting on the many ways you have grown over 2021. Consider the challenges and struggles you have faced. Wield the appreciation you have of yourself as a kind of resolve to support yourself in the best way you can this year, nourishing and discovering what is already within you.

As we feel the Earth lurch disturbingly into irreparable imbalance as a result of our “never enough” mindset and irreverence for life, as we process the persistent reminders of how lightly we are here in this unremitting pandemic, as we witness human hubris and ignorance and cruelty sow starker political, economic and racial division, may we channel our grief and rage into greater humility and loving-appreciation for what we have been given. May we rededicate ourselves to caring for and cherishing what is already here.

The answer to life, the universe, and everything (or… what I talk about when I talk about yoga). September 5th, 2021.

What do we mean when we say yoga?

What is yoga really?

Why does it matter for us to know?

To say that yoga is stretching is like saying that reading is turning pages. One can read without turning pages at all. And although turning a page may be a helpful skill when it comes to reading, it does not describe the action or the function of reading.

There are a number of reasons why a better understanding of yoga could benefit us all, even those who do not particularly like yoga or practice yoga. For one, yoga is deeply misunderstood by most Americans (including many yoga instructors) and since white colonialist nations have a deep-seated habit of extracting something desirable from another culture or country while showing very little interest or respect toward the intrinsic spirit, cultural context, historical roots, and the land and the people to which it originally belongs, we owe it to the betterment of the world and ourselves to become more informed, more reverential, more culturally sensitive planetary citizens. What’s more is that, by doing so, we may find that what yoga has to teach us beyond the pursuit of physical flexibility is of utmost relevance to the difficulties that we face in the world today.

So what is yoga?

Yoga is the oldest recorded mind-body philosophy in the world. Relics from the Indus Valley (think northeastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, western and northern India) date as far back as 3300 BCE. That’s over 5000 years ago. Yoga is having a pretty good run.

Though we think of yoga’s initial development as primarily centered in India, more recent scholarship reveals relics as far flung from the Indus Valley as portions of northern Africa and ancient Egypt, where a similar tradition took root referred to as Kemetic yoga.

Yoga as we know it today is the culmination of a long and varied history, branching out in many directions, evolving and adapting in a number of ways. For instance, the Buddha was a dedicated student of yoga in India during the 5th century BCE who evolved the philosophy and practices of yoga through his insights into mindfulness and the nature of suffering. Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, also an Indian yogi and scholar who lived as recently as the late 1800’s through the 1980’s, had an equally profound impact on the evolution of yoga when he quite literally set it into motion by popularizing meditative movement as a central avenue of yoga practice.

The 14th Dalai Lama, who most of us are affectionately familiar with, is the current head monk of Tibetan Buddhism, a lineage drawn from, and building upon, tantric forms of yoga. Equating the word “tantra” or “tantric” with esoteric sexual rituals is a perfect example of the profound ignorance and distortion of eastern wisdom traditions by westerners in the past two centuries. Tantra (Sanskrit) means “to weave,” referring to the weaving of liberative wisdom into embodied practice. Tantra yoga emphasizes the use of mantra and visualization to embody beneficent states of being such as compassion, generosity, equanimity, and tranquility.

Zen is a further continuation of yoga, the result of Buddhism coming into contact with Taoism and Confucianism in China during the 6th century CE. Although Taoism, qigong, and Traditional Chinese Medicine developed in China independently from yoga and Ayurveda in India, the two systems mirror one another in striking ways, and once they directly intersected, each influenced the other.

Only in the past two centuries has yoga come into direct contact with the Western world and, as a powerful mind-body paradigm, yoga is having just as much of a molding influence on the west as the west is having on the practice of yoga.

With the rising popularity of yoga in America comes some concern that yoga is religious in nature or that it constitutes a religion (is it appropriate in schools? does it conflict with my religion? etc). Yoga, in its most rudimentary context, has no theological or sectarian orientation. Within the basic psychology and praxis of yoga, you will find neither an invitation nor a requirement for belief in God or deities.

Confusion arises because yoga developed over thousands of years intertwined with a number of religious traditions (some theistic and some non-theistic) including but not limited to Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Indeed, there are many practitioners in the world who view yoga as their religious path. Furthermore, there are those who engage yoga as synergistic with their principal religious path, including a number of noteworthy Christian theologians such as the renowned Trappist monk Thomas Merton, Passionist priest and historian Thomas Berry, Benedictine Brother David Steindl-Rast, Irish Jesuit Father William Johnston, Spanish Roman-Catholic priest Raimundo Panikkar, American Jesuit priest and Zen roshi Robert E Kennedy, Indian Jesuit priest and psychotherapist Anthony deMello, and Quaker author of “Eastern Light” Steve Smith, to name a few.

Should we choose to view yoga from a multicultural and interfaith perspective, we might see the richness of a practice that has passed through the hands of some of the world’s greatest spiritual teachers, shaped and informed by multiple cultures and wisdom traditions. Because yoga is capable of religious impartiality while inviting us into greater intimacy with life and with ourselves, it is both compatible with and supportive of all faith traditions. This is why we find yoga practitioners of all persuasions throughout the world, be they Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, atheist, Buddhist, Pagan or agnostic. Yoga as a holistic worldview, a mind-body science, and a praxis of wellbeing long preceded the birth of organized religion and it remains a practice that can be fully engaged today with or without a religious orientation in mind.

Okay, so what is yoga?

The Sanskrit word yoga consists of two root words — one means to yoke and the other means to concentrate. Both meanings describe the same action.

To yoke is to unite, to bind together, to harness (such as using a wooden beam to bind the strength of two oxen to pull a plow). Yoga is the power of integration, the weaving together of all our human faculties to come into direct immersive contact with life, with our experience, with ourselves, and with each other.

The word “religion” stems from a similar verb, the Latin religare, which means to rebind. To yoke oneself again and again to the intimacy of being, in its most radical fullness, is a shared compass point for all of the world’s spiritual traditions. What makes yoga unique is its emphasis on practical, embodied methods that harness our capacity to experience the fullness of life.

To develop our innate abilities, to become skilled at anything, requires dedication and practice. Yoga’s second root word is concentration in the sense of focusing one’s energy toward a specific outcome. Discipline, in its healthiest expression, simply means to care. If we want a relationship to endure, if we want to keep our teeth, if we want to succeed in our vocation, then we must have the discipline to treat these things with the level of care that reflects and fosters their true value. Yoga is the discipline of taking care of the life we have been given, the discipline of realizing its true value.

Many of us have a desire to feel peaceful and at ease in our being, to experience joy and wellbeing in our day-to-day life, to engage with our suffering in a way that leads to healing, to have a relationship with life and with death that illuminates an abiding sense of belonging. What we often fail to see or acknowledge is that we cannot possess these graces without committing time and energy to their cause. Taking care of your life is a kind of work you have to show up to. The payoff is beyond any kind of wealth you can conceive of.

Sometimes we have to feel the full gravity of the consequences of not showing up to the labor of taking care of our lives in order to finally give it the level of priority it deserves. Yoga as a worldview affirms and underscores the responsibility of each individual to engage in the labor of their own wellbeing towards the wellbeing of the whole. As a praxis, yoga gives us a set of life skills, accessible practices with measurable results, for engaging the work of wellbeing in a tangible way.

We come into this world equipped with a body, a mind, a heart, and a nervous system. These are the mechanisms through which we experience our lives and interact with the world. With proper care, understanding, and skill, these human faculties are conduits for deep connection and life-affirming states of being like tranquility, clarity, compassion, wise discernment, creative spontaneity, fearless sincerity, and equanimity. Yoga is like an owner’s manual for having a body, a heart, a mind, and a nervous system. The practice of yoga is a way of coming into relationship with these primary elements of our being, of learning how to take care of the instruments through which we experience both our inner and outer worlds so that we have a clear healthy signal.

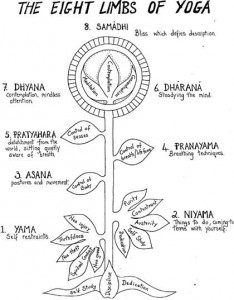

Yoga makes use of four primary, interconnected modes of practice:

- Engagement of breath as vital force and anchor for awareness

- Understanding the true power of mind and the nature of suffering through meditation in stillness

- Moving meditation as embodiment of meditative principles

- Fostering life-affirming states of being through practice (Non-aggression, non-reactivity, candor, mental clarity, compassion, equanimity, contentment, non-greed, introspection, loving-awareness, and zeal)

Let us, here and now, entirely rid ourselves of the image of yoga being the ability to touch the sole of your foot to the back of your head. What, in the grand scheme of things, is the value in that anyway? The extra-bendy fitness-obsessed yoga popularized in the West is at best a dilution or distortion of the practice and at worst a misapprehension that contains unconscious echoes of racism and colonialism.

In the early 1900’s, Indian scholars, researchers, and master practitioners of yoga such as Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, Yogendra, and Swami Kuvalayananda set out to renew the cultural practice and spirit of yoga as a positive and empowering expression of Indian nationalism in response to the dehumanizing exploitation of British colonizers and racist stereotyping of the Indian people throughout Europe. India was ruthlessly and systematically bled of its wealth and resources, exploited by European colonizers on the one hand and labeled “lazy degenerates” on the other, and the Indian pioneers of modern yoga were inspired by the global physical culture movement to further develop and refine the meditation-in-motion aspect of yoga as a way to revitalize the spirit of the practice in the hearts of the Indian people.

Physical culture was a health movement that originated in the 19th century in response to the rise in diseases of affluence affecting the sedentary lives of white collar workers and the exorbitantly wealthy in bloated colonialist countries. With the rising popularity of hatha yoga in India (hatha refers to an emphasis on physical and movement techniques), westerners took interest by adopting the most extreme elements of yoga as gymnastic exercise while largely relieving themselves of the meditative foundation of yoga as well as the practice of embodying its fundamental ethics.

There are upsides and downsides to America’s obsession with the movement component of yoga. On the one hand, we are so intensely divorced from our bodies, so over-identified with our dispersive minds, so truly sedentary, that movement practice is essential and powerful medicine for us. It is, in this regard, right for us to be so heavily attracted to and resonant with the practices of yoga that help to bring wellness to the physical body. For those of us who feel dissociated from our bodies, moving meditation is a vital healer, and a necessary prerequisite for skillfully engaging in the labor of reaping the cardinal benefits of meditating in stillness.

It is critical for us to understand, however, that the postures and stretches in yoga are meant to embody the basic principles of meditation: concentration, relaxation, elasticity (allowing energy and experience to flow through unobstructed, with awareness), and self-inquiry / self-transformation that is grounded in spacious awareness, clear-seeing, and unconditional compassion.

Stretching and postural practice in yoga is about caring for the body, connecting to the body, liberating the body, and integrating the mind into the body; relieving suffering and creating the right conditions for wellbeing; releasing cumulative tension and life-long habits of constriction; dissolving physical-psychic-energetic blockages that arise from stagnation, trauma, and habitual reactivity; soliciting flexibility in the spine and the body’s tissues to promote circulation of fresh fluids, oxygen, and the free-flow of vital energy; generating embodied presence, awareness, proprioception, interoception, coordination and stability; developing sensory awareness and focusing the mind through the body; balancing the nervous system with rhythmic movement-based breathing; and practicing embodiment of life-affirming states of being such as tranquility, loving-awareness, clarity, and equanimity.

What is deeply problematic about popular western yoga is that it is extreme and performative. This heavily conflicts with the true spirit and essential altruism of yoga. Colonialist nations have stripped yoga of its most vital components to reinforce its own dysfunction. I see practitioners engaging yoga as another opportunity to dominate, subjugate, judge, and aggress their bodies rather than engaging yoga as a means of listening, understanding, and caring for the body.

The aggressiveness that we cannot shake in the western world is fueled by fear and self-loathing, and the insatiable drivenness and desire for superiority that comes of it. Subsequently, yoga becomes another purveyor of attainment, vanity, competitiveness, greed, harsh self-judgment, inexhaustible compulsion to prove oneself and improve upon oneself, and prejudice towards bodies that do not conform to what is consciously or unconsciously perceived as superior (white, lean, fit, tall, symmetrical, privileged, and free of perceived disability, illness, weakness, impoverishment, or signs of aging).

I am not saying that you cannot engage in a physically vigorous or extra-bendy yoga practice in a way that upholds the integrity of yoga. I’m not saying that fitness yoga is not beneficial or that it is inherently racist or colonialist. What I am saying is that Americans are attracted to taking things to extremes because it is a function of our gnawing discontent.

Colonialist nations are built on craving, violence, and insecurity. We can never have enough. We can never be enough. We are relentlessly chased by a better, mightier, more sanctified version of ourselves. We cannot be at peace. We are frightened out of our own bodies and our own hearts by the cruelty of loathing ourselves into a better version. Our sense of connection, refuge, and fulfillment is thoroughly compromised by our unwillingness to do the courageous and loving work of being at home with ourselves and being at home in the world.

We must ever fill the void with the empty calories of scrolling and entertainment and accumulation. We must ever aggrandize ourselves to feed the hungry self-loathing. More stuff, more achievement, more work, more fame and followers, more knowledgeable, more right, more woke, more disaffected, more self-sacrificing, more good, more wealthy, more sophisticated, more trendy (yoga and goats, yoga and dogs, yoga and heat, yoga and wine, yoga and acrobatics, yoga and essential oils, yoga and heavy metal, yoga and… and… and… and… and).

Yoga exalts in the truth and power of simplicity. The practices of yoga are a kind of decluttering. There is a special irony in feeling we need to add something else to improve upon the unadulterated simplicity of yoga practice.

How can we see the fullness of life, how can we see the preciousness of what is right here inside of us, when we cannot see past the clutter? Yoga clears a space to let life come in.

The claim that physically strenuous yoga is “advanced yoga” is a dead giveaway. That is not what yoga is for. What advanced yoga really looks like for westerners is to remain in a prolonged state of silence, stillness, and receptivity. This is the heart and apex of yoga. Attending to the troubled waters of our minds is a much more pressing concern for us than the ability to perform a headstand.

The very first yogis, millennia ago, discovered wholeness and an unspeakable connection with life through the practice of concentrating the mind.

The root word concentration in yoga (yuj samādhau) has a double meaning: the discipline to focus one’s energy toward a specific outcome and absorption in the absolute now. What yogis through the ages have discovered is the clear, calm, luminous mind that arises with practiced concentration. This is Big Mind, the spacious awareness that disarms and dissolves compulsive mental chatter, distraction, fixation, and rumination. When the mind is stilled through practiced focus, we can really be here with what is right in front of us and we can really be with what is right here inside of us.

Luminous awareness of marvelous existence.

So much is invisible to the small mind, the restless, agitated, dispersive mind. Our addiction to stimulation, speed, and accumulation holds us hostage from the deep peace, wisdom, and connection that is our birthright. We are as fearful of peace as we are fearful of the discomfort of meditation. We might prefer that spiritual materialism, spiritual bypass, and spiritual elitism rescue us from the discomfort of having to actually be with ourselves as we are, actually be with life how it is.

What we fail to understand is that through the discomfort and labor of meditative stillness come the powers of spacious awareness, deep concentration, abiding tranquility, and unyielding compassion, all the alchemical agents that we need to transform suffering and constriction into healing and liberation.